This week from 13 – 19 May around the UK and beyond, ‘Mental Health Awareness Week’ will take place. Alongside all the wonderful organisations who champion and raise awareness of mental health issues, this week will provide an additional platform through which we can all, in our different ways, help shine a light on this crucial aspect of our health and wellbeing.

The Big Draw will celebrate its 20th anniversary next year, and throughout its existence our incredible and creative event organisers have always highlighted certain themes and issues in their work e.g. migration and refugees, environmental issues, intergenerational themes and so on – mental health has always played a crucial role. This is hardly a surprise given that mental and physical health combined have been proven to be so crucial to our overall wellbeing and our positive experience of what it means to be human.

This year in 2019 we were keen to encourage more of our event organisers to explore themes around the inter-connectivity between health, creativity and wellbeing – thus our festival theme this year ‘Drawn to Life: Health and Wellbeing’. It’s a broad theme intended to appeal to those working in a variety of formats and settings, a theme that works across sectors as we do and one that is for everyone - individuals or across communities.

I was encouraged by our theme for this year’s Big Draw Festival and Mental Health Awareness Week to share my own personal story – in my case, of living with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

- Kate Mason, Director, The Big Draw

I have never written about this in any way or shared it on any public platform, but it feels right to do it at this time in my life. Perhaps now as an older woman I simply just care less what other people think of me, so am less concerned about being ‘judged’ in some way. Part of it also is that as Director of the charity The Big Draw I remind myself constantly that I am in a privileged role and should aspire to do this role, and the charity, justice. Yes, I always need to try my utmost do the right thing to help nurture the charity, but there is also something owing to being ‘authentic’ and honest as an individual – and if you are in a role where you are able to publicly share words of support, understanding and solidarity - perhaps you should.

This is the starting point to my own personal story and experience of living daily with OCD.

I became aware that I had a heightened awareness to safety as compared to other children quite early on, probably as early as at primary school, but I didn’t think about it in any great depth. At secondary school I would sometimes undertake various counting or specific thought sequences – all at this time ‘invisible’ externally; entirely internalised with no physical manifestations. I was reasonably bright – not the super-bright child who seemed to walk everything – but I worked hard, was good at focussing and was generally seen as a solid ‘all-rounder’.

I had a very creative childhood with my two younger sisters – spurred along by a mother who had herself been denied a place at art school (not for ‘nice girls’ when she was growing up) and with a father who worked abroad most of the time. We all spent a great deal of time drawing, painting, sewing, making up stories and books with illustrations, devising fantasy worlds and maps, codes and generally enjoying the freedom of a childhood in a time free of the current restrictions that come with contemporary modern city living. Of course it wasn’t all idyllic though, and like any other family we had our own challenges.

What I did know by the time I was a teenager was that I wanted to be a Barrister (because I knew I was good at arguing my point!) and a fashion designer– something where I could draw and design fashions and then make them into something tangible I or others could wear. I felt at this time very strongly that I was very much a person of two halves – the ‘sensible’ more focussed, quieter and pragmatic half – and the ‘less sensible’, less linear, creative, more confident half. I never did make it to be a Barrister or a Fashion Designer (although I do still like arguing - or rather making a case – being an advocate for a cause - and I do still sketch, sew and love making clothes!)

The point was that, like many other people, I identified early on that being creative was a crucial outlet for me and was important as part of my own personal balance and overall well-being.

At that early age the ‘two halves’ really did feel very different and in opposition but as I matured into an adult I better embraced these different aspects to my personality and understood how I could apply them within a work environment. After graduating I knew I must at all costs find a job that enabled me to be creative in some way and be surrounded by what I termed back then as ‘interesting people’(!). A fuller description would be that I felt most comfortable meeting and being in the company of people who were naturally curious in nature, mercurial of thinking and happy to allow themselves to explore their own creativity in different ways.

Meanwhile in the background the OCD was always there. At University all my flat mates and close friends knew – or rather thought they knew. In actuality them witnessing me switching the light on and off in a sequence or checking the front door a number of times were the tiniest speck on the tip of a mammoth sized iceberg. When I started work, colleagues would see these tiny flashes externalised from what was going on in my head and might say – ‘how funny - we’re all a bit OCD aren’t we’ or ‘she’s so quirky’. They said it in fondness, never out of spite but it still rankled - in particular the phrase ‘a bit OCD’ is never going to be a winner with a sufferer of OCD.

My career progressed and I worked hard. The physical manifestation of my OCD was present only in my home life and only really spilled over into my professional work life rarely - when security was involved. So colleagues would smile and say ‘oh it’s just Kate checking the doors or taps again’ so they wouldn’t grasp the bigger picture I grappled with daily - and why should they? I was glad they didn’t, and if I needed to do physical actions alongside any internalised counting or checking I’d always ensure I was on my own.

The OCD always was and is focussed around security, precision and responsibility and whilst my ability to work and maintain a professional career has thankfully never been impacted, my home environment was a very different scenario. By my mid 30’s I was wasting probably between 30 minutes to an hour in total over the course of one day every day with various complicated and ritualistic checking routines around the house.

I remember feeling very lucky that unlike friends who had severe OCD and were unable to function sufficiently to undertake a job or even leave their house, I was unscathed in this area other than needing to face the terror of locking up an office each night – a tiny thing in comparison to the struggles of others. My more ‘sensible administrator’ ordered self, knitted alongside my creative side that was (is!) always willing to take a leap of faith, helped me keep on the straight and narrow as I saw it. I felt lucky.

My work and the jobs I had during this period of my 20’s and 30’s were absolutely fundamental in gluing everything together for me. They were all across the arts, heritage and creative industries sector and whilst, like in all jobs there were dull bits, crucially it enabled me to ‘feel useful’ and fully use my ‘two halves’ and be both creative, and imaginative as well as use my skills as a strategist - a sort of unruly fluid type of order! Alongside my passion for arts, heritage, scribbling out ideas on paper, sewing and other activities, this maintained my own type of balance. Not a perfect one to be sure. Up to an hour a day is a lot to lose every single day, but at the time it seemed to be a fair trade-off.

Then in my late 30’s my self-constructed creative cocoon took a battering. My OCD, which had always been an issue but one at a level I was willing to live with took hold, and instead of being something I found ‘annoying’ but could cope with, morphed into something altogether more destructive and terrifying.

Like thousands of other women, I suffered a miscarriage. I was 37 and was utterly devastated. We’d got past the ubiquitous 12 week hurdle and thought we were in the clear and the wrench and impact of the loss on my psyche caught me utterly by surprise. I was a strong person who holds things together; how could I be so weak and let this upset me so fundamentally? How could this happen?

The event triggered a dramatic change in the pattern and manifestation of my OCD: my one hour rapidly bloated to a 3-4 hour prolonged ritual every evening – assisted by the fact my partner worked nights and there was no one to stop me. Sometimes I would stay up all night repeating routines: they became increasingly complex, with more and more layers to get ‘just right’ or risk having to start all over again. Under duress from my partner I eventually visited a doctor and quickly found myself assigned to a local authority-linked organisation for a course of CBT (cognitive behavioural therapy). I was lucky: many people wait huge periods before they are offered CBT, it being very much a geographical postcode lottery as regards provision. I had a number of successive rounds of CBT whilst continuing to work. I was grateful for the LA CBT provided but the honest truth was it just didn’t work for me and felt like a terrible waste of everyone’s time and resources.

Life and work moved on and I became pregnant again and was delighted to be blessed with a beautiful little girl. My OCD remained as aggressive and bullying as ever and sleep, difficult enough with heightened OCD, and a small baby became virtually non-existent. I’d make excuses to go out the house with the baby early - i.e. first - to avoid having to do all my increasingly stressful checks. I’d check under the bed every night for murderers, and was reassured by a bronze statue that sat nearby ‘just in case’. I could easily spend 20 mins gazing into the oven to ‘make sure’ the cat wasn’t stuck in there, and another 20 mins on an elaborate door-locking routine - and that was before I’d even started on the gas hob, windows and taps. Needless to say we went through a lot of tap washers in our house!

I felt more than ever at this time that if it hadn’t been for my more creative, resilient half things would have become a lot worse for me. I believed at this time that my ordered, calm and organised half was broken. It could not help me improve my wellbeing. I was at wit’s end: unable to heal, unable to change, and utterly frustrated. However, my passions for art, making, scribbling, mapping ideas out, visualising strategies through sketches, stitching and sewing continued and although they could not heal, they helped a lot – as did working and keeping busy. They were, and are, my own personal lifeline.

At this point, given the failure of my CBT to date I’d been persuaded to attend a local OCD support group. I’d been initially sceptical but I did warm to it. Not because it particularly helped me glean anything new into my own OCD, rather because of the bunch of wonderful, extraordinary, funny, warriors I met there - and I call them warriors because they are, for just battling to get out the house and arrive at the session was a huge achievement for many. Their humour and ability to laugh at the ridiculousness of all of our positions whilst fighting these demons imbued us all with a certain strength and camaraderie.

It was when my baby was around 6 months old that it was suggested I might be a good candidate for research being run by Dr Fiona Challacombe – a research fellow and clinical psychologist working at King’s College London and the Maudsley Hospital in London. The work focused on postnatal mothers with OCD and the impact of OCD on parenting and families. Things fell into place and in exchange for my time as a subject contributing to the research, I was offered a new round of much more in-depth and tailored CBT with Fiona herself running the sessions.

I accepted, initially somewhat reluctantly given my previous experience, but there was no comparison: my experience with Fiona leading the sessions was far more effective than the CBT sessions I’d endured previously. This likely has a lot to do with the skills and experience of Fiona (and indeed passion for her research) but does also underline the well-worn premise of how important it is to find the right therapist for you. I was lucky.

"Many women experience onset and intensification of OCD in the context of pregnancy, pregnancy loss and motherhood. It is a stressful enough time of life without the demands of this understandable but unnecessary problem heaped on top. When Kate took part in the project, the concept of perinatal OCD wasn’t well known, either amongst professionals or women. Thanks to her and other participants in the study, we are now able to say that it is a very common problem affecting many women (and men), and that as for Kate, it can be treated effectively with CBT so that parents can enjoy parenthood again."

- Dr Fiona Challacombe, research fellow and clinical psychologist

My sessions with Fiona and the exposure therapy I did around this did help me to a great extent. I improved enormously and managed to rein the OCD back in. Regular exposures at flashpoints were recommended: I did them. Medication was suggested as a possibility to aid recovery: I took it all. Meditation and reiki were proposed by some: I didn’t – not for me ;-)

And the result? I did not manage to vanquish it entirely. OCD sadly remains a constant, if now greatly diminished presence in my life. Now and again I do still panic if, for example, I am driving the car and imagine I have just run over a cyclist (a previously common fear). The difference now is that I don’t drive back to check, but rather am able to rationalise it given all evidence to the contrary.

These days my symptoms have retreated, and re-appear only when I am extremely tired or at specific times of the day and/or with specific tasks, especially locks (and only for a few minutes). But these are still minutes lost which I needn’t lose, and I have to remain constantly vigilant to ensure I am not covertly caught unawares and pulled back into the dark.

All of us live with our own demons, challenges and daily battles. I would say to you all that perhaps beneath the veneer of that calm, focused and driven individual you know from the gym, the perfect mother from the school run or the supercool CEO at that partner organisation you’ve just started working with - not all might be quite what it seems! None of us are robots and we all experience stresses and challenges in our lives. We all could be a little kinder to ourselves and others. More people need to speak out about their own experiences to help normalise these issues without fear of judgement – to do it for their families, friends, colleagues, people and communities around them.

In this current ‘Mental Health Awareness Week’ to all of those out there now, and every single day – all those warriors battling invisible insidious demons – I say: stay creative, and I salute you all!

___________

Kate Mason, Director of The Big Draw and Mother to two wonderful little girls

___________

Have you been inspired by Kate's story and The Big Draw Festival 2019 theme: #DrawntoLife?

Why not join our global Festival in 2019? Registration is now open! Find out more about the benefits of becoming an organiser here and other ways to support The Big Draw's mission here.

Are you suffering with symptoms that sound similar to Obsessive Compulsive Disorder? You can find out more about OCD and other Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviours through OCD action, OCD-UK and Rethink Mental Illness.

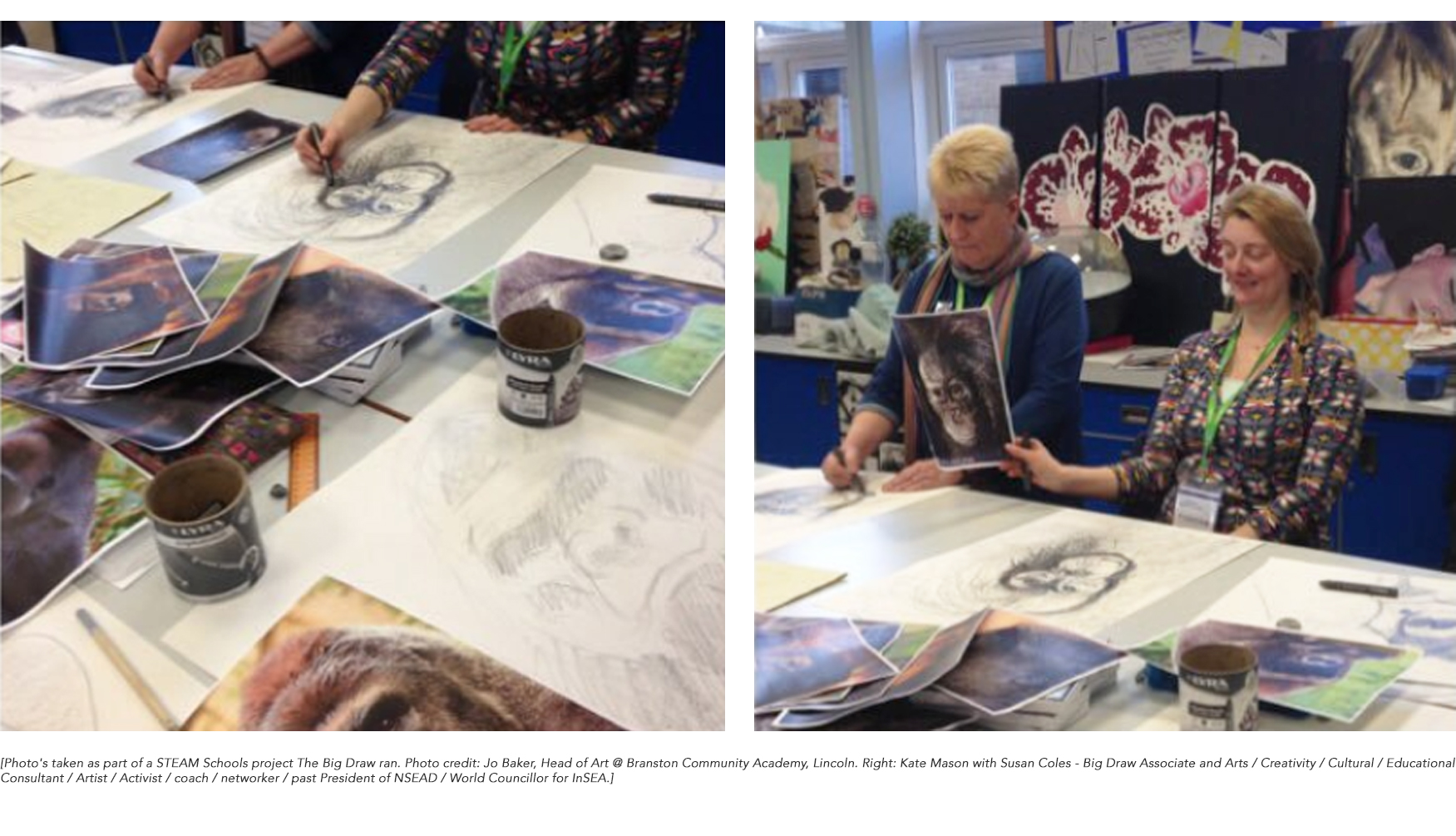

Want to find about more about the importance of drawing in Schools, STEAM and The Big Draw's campaign for creativity? You can read more here.