Born in 1945 in Berkshire, Posy Simmonds drew from an early age. After studying at the Sorbonne and Central School - now Central St Martins - respectively, she entered the world of print journalism, working as a cartoonist for several British newspapers from the late 60's onwards. Often compared to the likes of Austen, Elliot and, most frequently, Thomas Hardy (upon whose work her own books are closely modelled), Posy is an astute modern satirist, combining words and visuals in her storytelling to mock and condemn the British middle-class.

Her satiric wit flourished within the pages of The Guardian, with whom she has been affiliated since the early 1970's; after several published strips, the 1999 publication of Gemma Bovery, a reworking of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, proved testimony to her observational skills. Simultaneously, Posy turned her talents to children’s publishing – notably her story of an ordinary, seemingly lazy cat named Fred, who leads an exciting double life.

Posy is an expert observer on the minutiae of everyday life, taking inspiration from passing conversations and phone calls overheard on public transport or in coffee shops. We couldn’t wait to catch up with Posy to talk more about her work, inspiration and influences - as well as a bit about her thoughts on the role of comics in society, and her hopes for the future of the industry.

Interview: Matilda Barratt in conversation with Posy Simmonds.

Cartoonist, writer, illustrator… You’re a woman of many titles! How did you come to do what you do? Was there a defining moment where you decided to take this path, or have you always had an interest in the field?

I was interested in cartoons very early on. One particular bookcase in our house attracted me. The bottom shelves, the ones I could reach, had bound volumes of Punch, some Victorian, some from the 1930s. I liked looking at the cartoons and, later, when I could read, puzzling over the captions. Other shelves had collections of cartoons by Giles, Pont and Ronald Searle. These influenced my own drawings, which always had a caption or a speech balloon.

I also read a lot of comics - Beano, Dandy, Topper, Eagle, Girl etc and many U.S. ones, passed on by American schoolmates (it was not long after the war and there were several US Air Force families living in the village where I grew up). My parents allowed me and my brothers and sister to read comics as long as we also read books. In those days comics were rather looked down on and you were supposed to grow out of them. (which, of course, I never did.) An early ambition was to be an artist. I went to art school, but studied graphic design and illustration rather than painting - I always liked the combination of words with pictures.

[Image: Posy Simmonds© World Upside Down,1987]

Could you tell us a bit about your process? When creating a comic strip, where do you typically start?

After leaving college in 1968, I began illustrating newspaper articles - an occasional one to begin with and then more frequently. These drawings had to be done at speed, often at short notice, no time for second thoughts - an excellent training and way of loosening up the drawing hand…and very unlike my college experience, where an illustration might be worked on for weeks.

Most of my work has been for The Guardian and includes a long-running strip about The Webers, Literary Life - a strip appearing in the Review section - and two serials (Gemma Bovery and Tamara Drewe). Both serials were subsequently published as graphic novels. Cassandra Darke is the most recent graphic novel. I’ve also written and illustrated children’s books, which include a comic strip format.

When creating a serial, I would start with a rough idea of the story and then begin drawing the characters in a sketchbook - a sort of casting couch - trying out different noses, expressions, hairstyles, clothes until there’s a sort of “fit”…there’s a moment of recognition, when I would think “I know you”.

Each episode was planned on an A2 layout pad. I would start by asking “What’s happening?” Then I’d make a rough storyboard, writing bits of narrative and dialogue, sketching characters, location and weather. I might write out the narrative four or five times, each time trying to get it as concise as possible, so that it didn’t take up too much room. Dialogue would be tested out loud to see if it sounded natural.

I followed more or less the same process when doing the weekly strips, although, as each strip was self-contained, I didn’t have to pay so much attention to continuity. Inconsistencies, of course, did occur and readers would write to point them out - as when I forgot that I’d given one character a vasectomy, or that the guinea pigs died in a previous episode.

Does drawing play a major role in your everyday life, as well as your career?

Yes. I try to draw every day and am a compulsive doodler (sometimes on bills and other important documents).

Who and what have been some of your greatest influences?

Ronald Searle, Saul Steinberg, Carl Giles; Beatrix Potter, Kathleen Hale. Also Thomas Rowlandson, William Hogarth, and Jean-Jacques Grandville.

[Left: Sketchbook works of Gemma Bovery taking inspiration from Lady Diana. Right: Sketchbook works of Cassandra Darke.]

I’m interested to know, with characters like Gemma Bovery and Tamara Drew, how do you go about distinguishing their identities and personalities - and does this approach differ from the process of developing their physical appearance?

The main characters are built up visually first in sketch books. Then I like to imagine their back story, their childhood, parents….even if these details aren’t used in the novel. Their personality and reactions come from asking questions like: why would she/he do that? How would she feel? Is she lying? Self aware? What does she hate most about her appearance?

Are there elements of yourself or people that you know or see in passing that (consciously or unconsciously) inspire your characters and their various personality traits?

I am not conscious of putting elements of myself in characters, but am sure that I do. I often draw people that I’ve seen in the street and the details of their clothing, hair, handbags etc come in very handy when composing a character. When I was doing The Guardian strip, if a friend or family member provided something I wanted to use, I’d ask permission and put their initials in a little bubble on the drawing.

[Images: Sketchbook studies from life.]

You have said before that ‘women in books aren’t allowed to be total rotters’. Could you expand upon, and perhaps tell us why you chose to go against this when creating your own female characters?

I said this rather absent-mindedly in an interview and immediately corrected myself, because it’s not true, there are plenty of female rotters in literature, from Greek mythology, fairy tales, Lady Macbeth, Mrs Norris (Mansfield Park), Mrs Danvers (Rebecca) Cruella de Vil… and so on. It’s true that society expects women to behave themselves…they are certainly more interesting to write about when they don’t.

Do you think that comics still have an important role to play in our society, despite the decline of print? How do you feel that the industry has changed since you first started, and what are your hopes for the future of the field?

I think that comics have a great part to play, both in print and digital form. In the past, the UK comics world was much less advanced than, say, Belgium or France, but in the last 25 or so years has caught up hugely. There are Comics festivals, exhibitions, shops, blogs and a generally raised interest. Encouragement comes from organisations like Laddeez do comics, an important women-led forum, providing mentoring, workshops, talks and awards. It’s a growing industry - over 5,000 titles were published in France in 2019. Even so, it seems that only the authors of best-selling titles can make a living.

Until fairly recently there wasn’t much overlap in the UK between newspaper cartoonists and Comics - they were two separate spheres. Drawing for The Guardian and mostly for the Women’s page, I didn’t encounter the difficulties that a lot of women had (and still have) breaking into Comics, a traditionally male domain. But things have been changing, it’s gratifying that, worldwide, more and more women are producing comics, especially graphic novels.

Technology has brought about the biggest change - drawing tablets, Photoshop, colour programmes, 1000s of typefaces to choose from; the ability to scan and send artwork anywhere in minutes. I’m from a pre-computer generation and prefer drawing and lettering on paper - which many younger people, of course, continue to do.

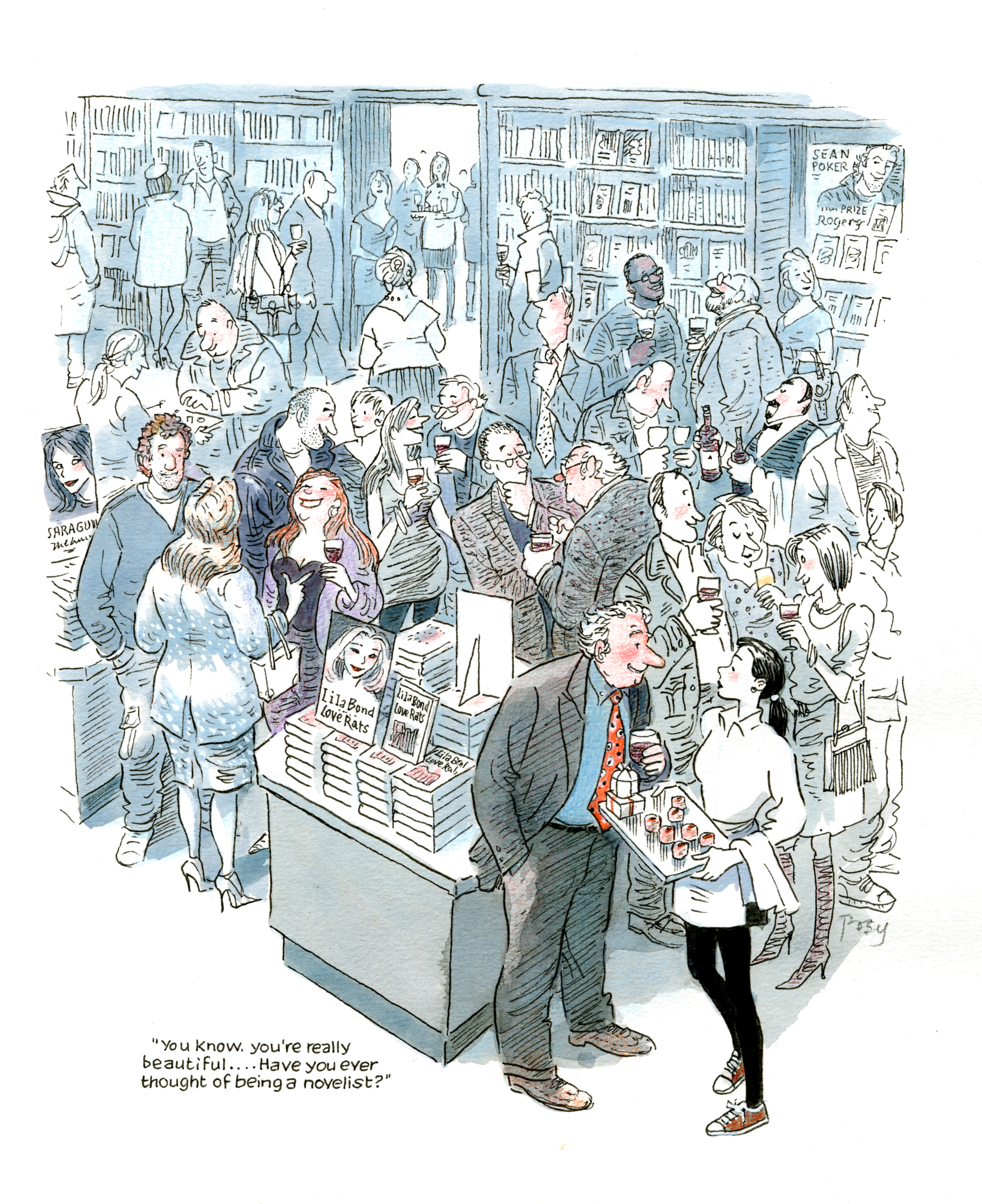

[Image: Posy Simmonds, The Guardian 2004, Literary Life 2]

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected you, personally and professionally? Have you found your relationship with drawing and creating has changed at all in this past year?

During the pandemic I’ve been isolating with my husband in London. Having always worked from home, Covid hasn’t stopped me from drawing or working on a new book, although I’ve found it harder to concentrate. The news is grim, time is slippery, weeks slither by, it always seems to be lunchtime. Like everyone, I miss seeing friends and family.

What would be your advice for aspiring cartoonists and illustrators? What sort of challenges and opportunities await the industry’s future generation of creatives?

Draw every day. Carry something pocket sized for sketching / jotting on-the-spot. Listen to the way people speak - it’s so easy now, people talk loudly on public transport, in the street and particularly on their mobiles. Radio phone-ins are particularly good for use of language. Watching TV interviews and talk shows with the sound off is very good for studying facial expressions, posture and gestures!

Thank you, Posy!

Registrations are open for The Big Draw Festival 2021: Make the Change! Find out more about the benefits of becoming an organiser here and other ways to support The Big Draw's mission here.