“…All children are artists and they only stop being artists if they stop believing they are… We lose an important medium of self-expression when we stop drawing.”

Ed Vere is an award winning writer and illustrator of Children’s books, including titles such as Max the Brave, How to be a Lion, Banana, and Mr Big. His new book, The Artist, is a “love letter to creativity” that aims to give confidence to young artists (and older ones too!). Alongside his books, Ed Vere is an advocate for arts education and is the co-creator of the CLPE programme ‘Power of Pictures’. Read on for an inspiring and insightful chat about picture books, live jazz drawing and the importance of creative confidence.

Interview: Lucia Vinti in conversation with Ed Vere

Photograph by Charlotte Knee

Hi Ed!

Congratulations on your new book The Artist being published! What was your inspiration was behind the book, and what it’s all about?

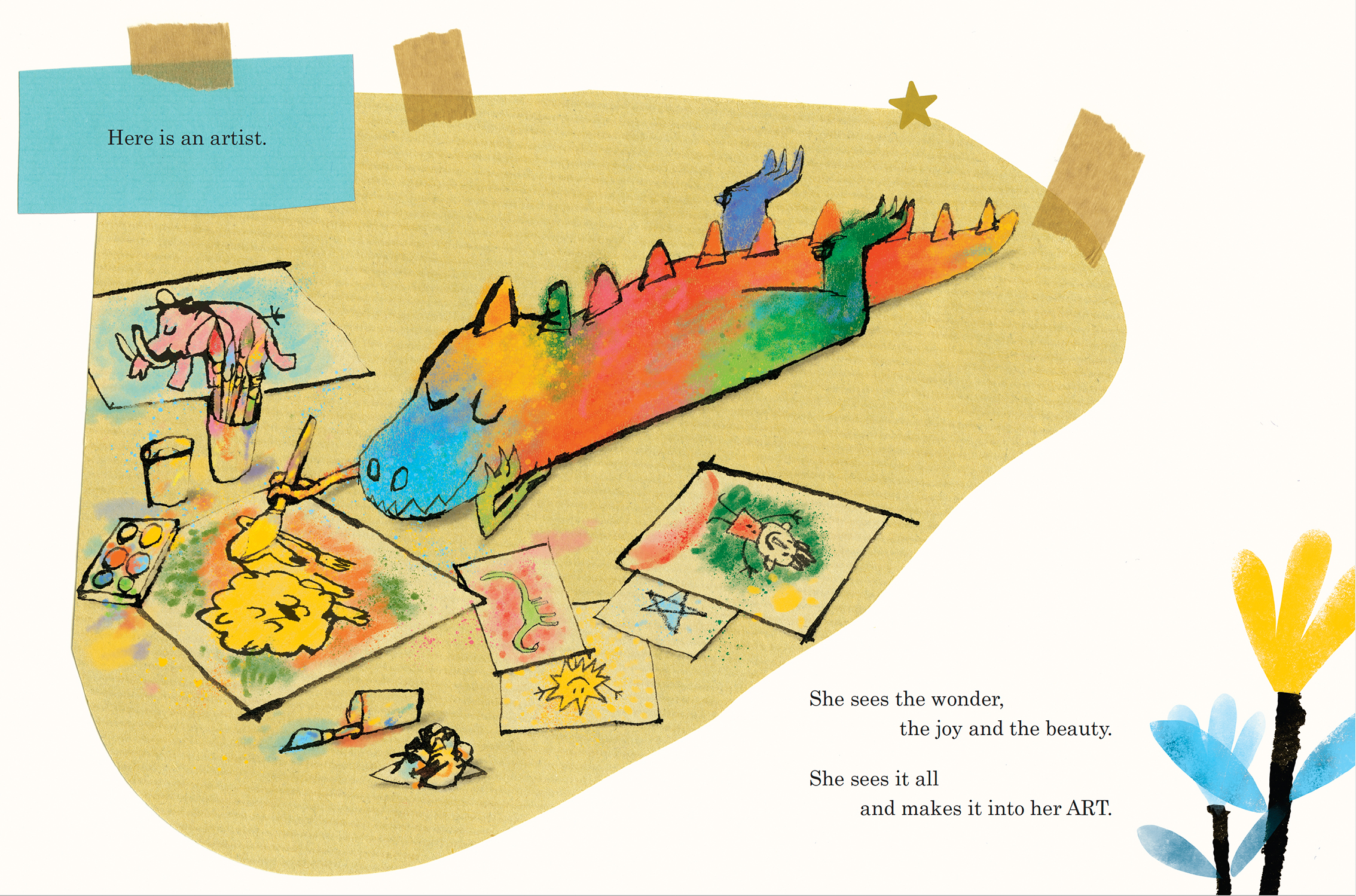

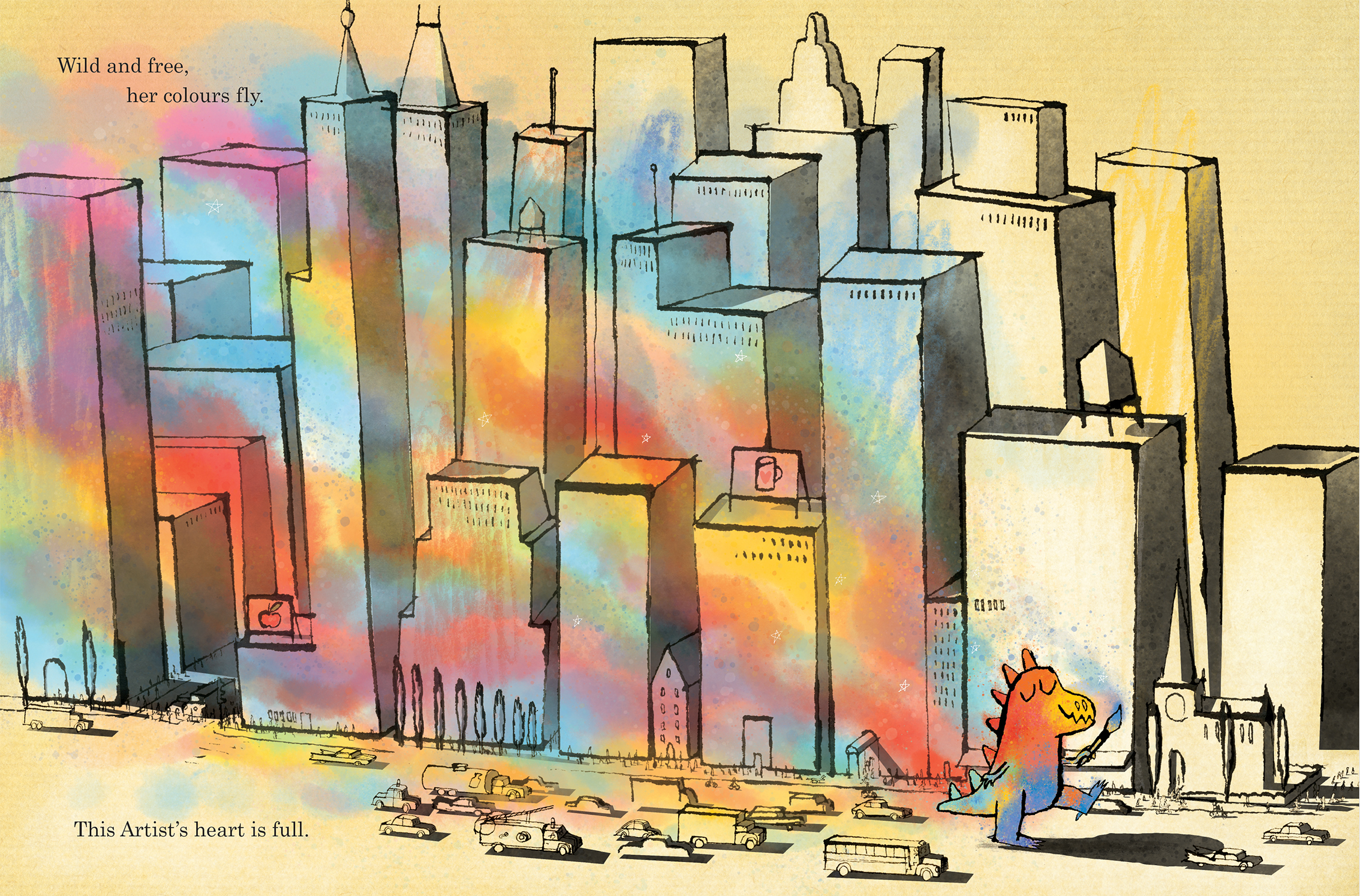

Thank you very much! Well, ‘The Artist’, was quite a while in the making… Back in the mists of time around 5 years ago I drew a picture of a dinosaur striding joyfully through a New Yorky kind of city with a swirl of painterly colour reaching out into the sky behind her and a line of text saying, ‘There are cities to paint!’. It felt like the final image of a book about creativity.

I’d been working with CLPE for a few years by then, co-creating a visual literacy programme together (more of which later). I had a lot of thoughts floating around my head about children drawing, how important it is, and what we can do so that most don’t lose confidence in their abilities around the age of 7 or 8 and give it up. It’s also a kind of love letter to creativity for older artists too. It’s for all artists of all ages.

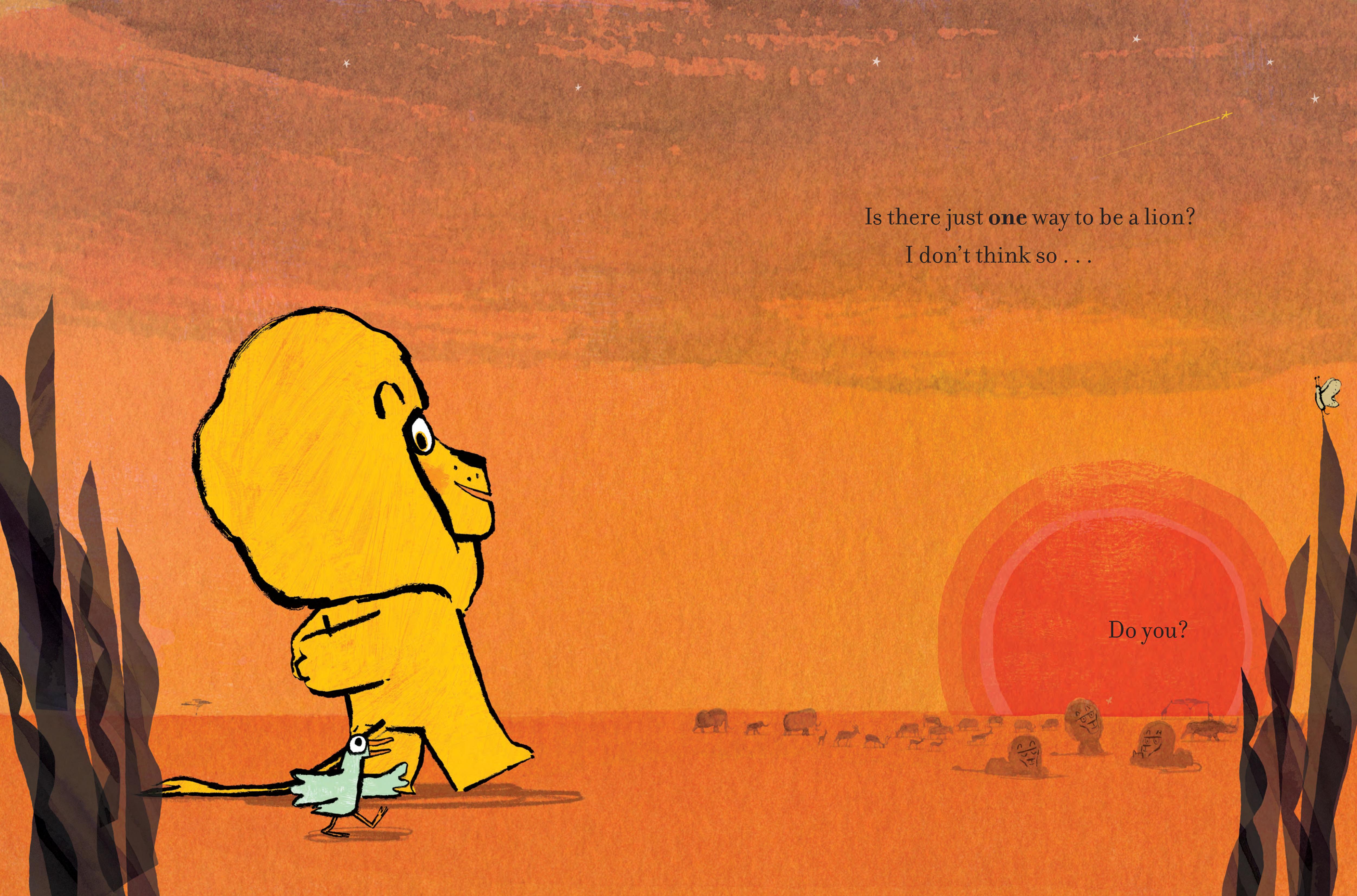

I taught in China a few years ago and was asked to give a talk to the upper school (11–17-year-olds). It was a great academic school, but perhaps largely preparing them for a corporate existence. I wanted to say that there are a multitude of options for how to live your life. Being an artist being one. To do that I tried to say what I thought being an artist meant, which is the question asked at the start of this book. I took the pupils on a loose illustrated tour through art history, from Ice age sculpture 40,000 years ago, through classical Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Renaissance, Impressionism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop, Minimalism and Conceptualism ending with Damien Hirst’s pickled shark. What links them all, I think, is that someone has made the decision to spend time looking at the world, thinking about what they’ve seen, slowly, without rushing, and then sharing a response - it could be written, sung, acted, danced, built, sculpted, painted, or drawn. That is what I think an artist is - Someone who decides to take time to look at the world, think about it, and then share their response.

I wanted this to be a positive message about creativity for all children… because all children are artists and they only stop being artists if they stop believing they are. I wanted to remind grown-ups too… because almost all of us loved to draw when we were young. Most of us stopped, for all sorts of reasons, perhaps not feeling good enough being one. Which feels like a terrible shame to me. We lose an important medium of self-expression when we stop drawing.

I wanted this to be a positive message about creativity for all children… because all children are artists and they only stop being artists if they stop believing they are.

As I was making the book we were going through the lockdowns, so I also wanted the story to remind us what a beautiful place the world can be, if we remember to notice it. I wanted my artist to see and feel the joy she sees in the world and then transmit it out again. I feel it’s important that children know that the drawings and paintings they make, which are pinned to countless fridges and walls across the world bring an endless amount of joy. Which is why much of the art in the book is drawn and painted on cut out paper and taped to the background, in the manner of a child’s drawing.

I’ve tried to make a wonderful and joyful story about what it means to be creative at all ages, and the joy it can bring to your life. I absolutely loved writing and illustrating this book, I hope that the joy I had making it transmits to all who will read it.

What were you like as a young artist?

I loved drawing and I still do. It was what I was best at… by far. I drew a lot. I think I was 5 when I knew I wanted to be an artist. I wasn’t academic at school, but more of a visual thinker. My classmates gave me a bit of cred for my drawings. I remember going through a phase of meticulously drawing scrambler motorbikes (wish fulfilment?) with big knobbly tyres, high mudguards and complicated engines. A drawing was finished when I’d neatly labelled Kawasaki or Yamaha on the petrol tank. I also remember drawing a downhill skier and a friend asking how I knew which way the knee bent… I hadn’t realised it wasn’t obvious. Maybe they were an academic thinker?

My father was an architect, so drawing was valued at home and the idea of growing up to be a painter was not seen as ridiculous. I loved to watch him draw, seeing his steady hand sketching out assured lines while from his other hand there’d be a cigarette building up its perilously long ash pile as he concentrated. I remember him drawing a squirrel in a tree above LA skyline at dusk, the taillights marked in red ink. It was magical seeing a drawing appear in front of me.

I was also incredibly lucky that the legendary Jan Pieńkowski (Illustrator of many classics; Haunted House, Meg and Mog, The Kingdom under the Sea) was a close family friend. We would visit Jan and David (his partner, my Godfather) often. Seeing Jan’s Aladdin’s cave of a studio was always a huge treat. The walls covered in sketches and drawings for whatever exciting new project he was working on. Endless mugs and jam jars filled with felt tips, cupboards heaving with art materials and shelves of amazing risqué French comics to be discovered when I was a bit older. We’d sometimes draw together, and Jan would subtly drop pearls of wisdom as we drew. Jan was a huge advocate of drawing from life. It teaches you to look at the world and makes you notice all the endless theatre of life. He would always carry a small moleskine notebook and sketch wherever he went - a habit I now have too.

[Drawing from life] teaches you to look at the world and makes you notice all the endless theatre of life.

For many years, from the age of 20 I used to go life drawing in Jan’s studio on Friday evenings. The great Satoshi Kitamura would also be in attendance. Satoshi producing merciless caricatures of us instead of drawing the model. We’d always be pretty supportive of each other’s work, but be able to laugh at the really bad ones. If Jan uttered the phrase ‘how brave’, you knew you’d messed up a drawing.

Seeing Jan and my father take drawing seriously as I grew up was a wonderful schooling. It gave me confidence that you could grow up and spend your life doing what you loved… drawing and painting. It’s part of the reason why I think author and illustrator school visits are so important. Seeing a grown-up who does these things for a living, shows that you can do it too.

Who’s your favourite artist?

There are so many. I tend to particularly love artists who are good with line. Dürer, Hokusai, Picasso, Matisse, Degas, Schiele, George Gross, Ellsworth Kelly… but the artist I’ve loved longest is probably David Hockney. I read his autobiography (Hockney on Hockney) when I was about 14, it opened my eyes to what being an artist meant and made me desperate to go to art school in London. I loved his line absolutely, but also his endless curiosity and constant reinvention. He is all about looking at the world through drawing. He’s entirely dedicated to the act of drawing, even his paintings are really drawings made with paint. I so admire his energy and evident love of life. His work abounds with joy. A real inspiration for me. An artist I’d love to meet.

You’re a patron of CLPE (Centre for Literacy in Primary Education) and have worked with them to create a scheme called Power of Pictures. Could you let us know a little bit more about the scheme and the work you do with CLPE?

I’m a huge fan of the amazing literacy work that CLPE do. Tirelessly advocating for reading and getting good books into children’s hands. About 12 years ago I had a conversation with Charlotte Hacking about how we might improve school author/illustrator visits. We wanted to find a way to make a more sustained project, rather than the usual hour-long visit. As we talked, we found a shared interest in visual literacy and both felt that it was completely missing from the school curriculum… along with drawing.

A large aspect of the ‘Power of Pictures’ programme Charlotte and I went on to develop aims to give primary teachers the understanding and confidence to see what pictures actually do, to use drawing constructively with children, and to (gulp) actually draw themselves. Many haven’t drawn since they lost their own confidence in it when they were 7 or 8. That loss of confidence can be passed on, and make drawing a daunting area. We try to break that cycle.

Pictures speak to children (older ones included). Understanding this can be the key to discussions teachers might not have thought possible. ‘Power of Pictures’ teaches that the pictures in good picture-books carry highly sophisticated, emotionally laden messages which are easily deciphered by children. They are a fundamental part of the narrative.

We’ve invited many brilliant author/illustrators to lead courses; Benji Davies, Chris Haughton, Nadia Shireen, Joe Todd Stanton, Viv Schwartz and Alexis Deacon being a few. The programme starts with an author/illustrator and Charlotte Hacking presenting to teachers for two days. We cover and demonstrate how ideas begin and how we go about developing them. Particularly, how we each work in different ways, and that children may need to also. We forensically analyze a picture book (one of our own), talking about how to unearth all the rich and sophisticated narrative that is happening in the pictures. Often, the written narrative is the teacher’s focus and pictures are bypassed - ignoring a wealth of highly sophisticated narrative information. Power of Pictures shows teachers how rich layers of pictorial information can be uncovered. How pictures can be open to highly creative interpretation, open to be interrogated, analysed and discussed by a class. Children naturally do this for themselves, they’re just not often asked about it. We speak about the editorial process and how important it is to analyse and then re-write your own work, and to listen to the opinion of others and bear in mind that you’re writing for an audience. We also, very importantly, get the teachers drawing, showing them how easy it can be to draw a character who expresses something. The idea being that if a child is wary of a written project, perhaps because grammar is hard, or spelling, instead they can draw a character and think about who they are. This way an idea can develop in a child’s head before a word is written.

The teachers take all this back to the classroom for a 12-week programme with their students where they’ll forensically deconstruct a picture book together, coming to understand how and why it was created. The children will then create their own picture books, using the tools we have shown their teachers. Writing, drawing, sharing their ideas, editing, producing and binding their own book which will finally be displayed on a school wall for all to see.

Photograph by Charlotte Knee

Why do you believe it’s so important to teach visual literacy in schools?

Education in this country works well for those who are academically minded – and pretty badly for those who think in other ways - Those who may be equally bright but think visually or spatially.

A huge part of changing this dynamic must be about changing the minds of teachers. Giving them the understanding and confidence of why and how to use drawing… and to actually draw themselves… so the children see a grown up draw in front of them and don’t learn it is a childish thing.

We understand complex expressions and emotions through drawings from a very early age, in ways we can’t yet do with the written word or spoken language. From the moment a child comes into the world they are searching for visual clues. Trying to understand if you are friend or foe, through facial expression and body language. Pictures speak this language fluently. Pictures intimate emotions, feelings and nuances that words don’t at a young age because of this sophisticated visual vocabulary (which we are constantly building). Pictures are open to subtle interpretation – there’s nothing concrete to get right or wrong - which means they’re open to discussion and there is no danger of shame because there is no wrong answer.

We understand complex expressions and emotions through drawings from a very early age, in ways we can’t yet do with the written word or spoken language.

Children are able to use this visual vocabulary creatively when they ‘read’ pictures and when they draw, yet we don’t harness either in the education system. When a child arrives at primary school most draw naturally and happily, freely expressing their emotions. The majority will have given up drawing by the age of 8 or 9 (believing there’s a right and wrong way – there isn’t). In doing so, they lose a vital form of self-expression which they don’t have another outlet for.

In an age when we are beginning to understand how vital good mental health is, it feels careless to be letting the innate practice of drawing slip out of our children’s hands. Neuroscience shows us that the right hemi-spere of the brain is where it’s all going on as far as our emotions are concerned. It’s the side of non-verbal communication and it also happens to be the side of the brain that we use when we are drawing. The two things are connected. ‘The right brain hears the music, not the words, of what passes between people.’ (Allan Schore)

Visual literacy deserves a serious place in our children’s education. Power of Pictures tries to address that. We hope eventually to make concrete changes to the curriculum so that drawing and creativity are taken seriously. Education should be about building fully rounded, happy people, not just cogs to fit into an economy.

You’ve previously worked with orchestras and jazz musicians to stage event that combine drawing with live music. These sound like so much fun! How did music help bring your drawings to life?

They are immense fun! it all started 10 years ago when a friend took me to see a Jazz group she thought I’d like. They were incredible… driving rhythms and insanely energetic, beautiful piano playing. I listened to them on repeat for 6 months. Then one day, madly, an email arrived from the piano player, Neil Cowley. His trio had been asked to put on a concert for children at Wigmore Hall. Neil asked if they could use Mr Big (my book about a large, lonely gorilla, who is also a dab hand on the keys) to base a concert around. (I don’t think Neil will mind me saying that he saw himself reflected in the hirsute protagonist). Anyway, I said of course… and can I help in any other way?

We had a coffee and devised an idea for a live-drawing, live jazz concert. Rehearsals were had emotionally matching each piece of music to each scene in the story, live drawn by me. The beauty of Jazz is that Neil, Rex and Evan could be flexible, improvising each piece so I could draw the scenes in an unhurried way. The music often syncopating with the rhythm of the drawing, and vice versa. It was beautiful to feel how the audience reacted to the deep emotional tone the music gave to each drawing, hearing them respond to the more emotional parts was genuinely very moving. We played grown up, exciting Jazz to many family audiences. The energy crackling through each was palpable.

I also worked with the great Britten Sinfonia and Hannah Conway to produce concerts of Mr Big and Max the Brave. Introducing children to classical music in an engaging way. Instead of a trio, on stage was a small orchestra. A big difference was that each musical piece was timed exactly… 2 minutes 37 seconds for an excerpt from Ligeti, for example. Each drawing had to time exactly with the piece. Insanely tricky. Ink was flying everywhere as I scrambled to get through each drawing. So much fun… so much intense concentration.

Music and drawing fit together well. It’s lovely to try and tell stories visually and sensorially, without relying on words. Children seem to love it too.

Is there something you find yourself drawing again and again?

People. I love sketching people when I’m out and about… Like Jan I normally have a small sketchbook on me. I find myself drawing all over the place, on the tube, in cafes, in the street, airports, galleries, when I’m travelling, etc. Just quick sketches trying to capture the essence of what’s there. Maybe a feeling or an expression on someone’s face. It doesn’t matter if it’s good or bad. It makes me to look at the world around me. And when you start to do that a lot, you end up doing it all the time, imagining how you might draw something or someone, what their body language is saying and how you’ll describe them with a few inky lines. You find that you start to notice all the endless small details that make life fascinating. All the theatre of life. If you always look, really look, you will never be bored.

I find that all this looking, scrutinising expressions, body language and the general theatre of life eventually works its way into my books.

How do you come up with your picture book ideas? Your characters all have such unique personalities - do you start with the story or character first?

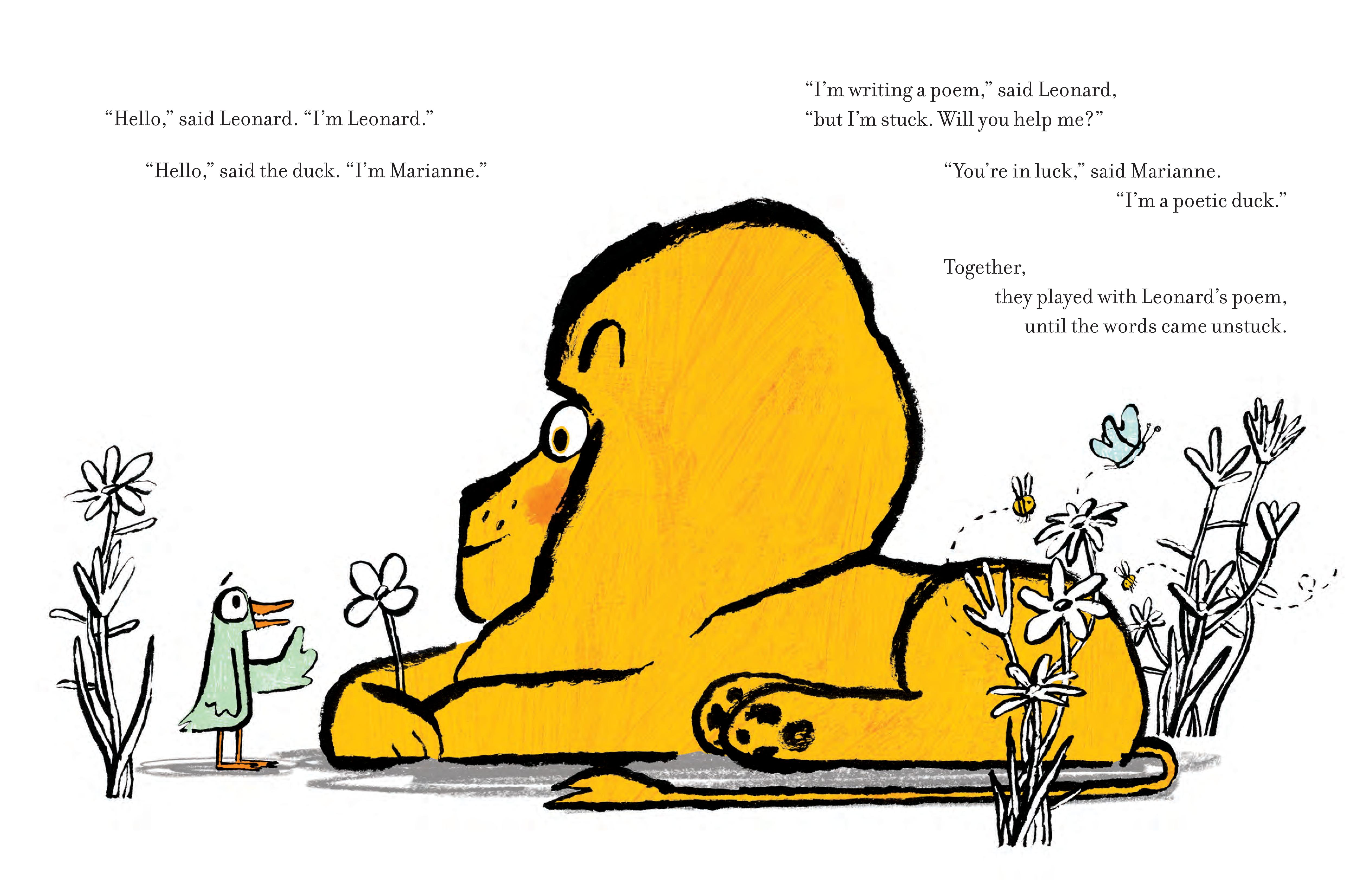

My books are very character based and always begin with a drawing rather than a plot or storyline. I don’t know what I’ll draw, but I normally start with an eye and work out from there. It may develop into a thoughtful lion trying to look brave, or a large Gorilla with an air of vulnerability playing a piano. Or maybe a young dinosaur who wants to make paintings for the world. All the drawing I do in my sketchbooks somehow filters into these drawings. Maybe something I’ve seen and drawn years before will become evident in a drawing at this stage. The key thing is that whoever I draw feels like they might have a story behind them.

Often a drawing goes nowhere, but sometimes the character will have something about them that I want to explore. Then I might have the start of an idea. I draw the character again and again, trying to work out who it is they are, feeling my way into what a theme or story might be. From there drawing and writing work alongside each other, as I try to hammer rough shapes into a more solid idea.

I spend a lot of time thinking, trying to be very loose. I often feel at that early stage that an idea is an amorphous cloud above me, constantly taking different shapes until it forms into a shape that feels right. If I try to describe it to someone, I risk making it too concrete before it’s ready. It can be a frustrating part of the process, but I’m learning that for me it’s vital to let it brew at its own pace somewhere in the back of my head for as long as it needs. When it’s ready, it all comes pouring out, which is a rare joy.

I often feel at that early stage that an idea is an amorphous cloud above me, constantly taking different shapes until it forms into a shape that feels right.

What’s the best and worst thing about being a children’s book illustrator?

For me it’s all pretty good. I absolutely love working as an author/illustrator. It can be very rewarding and feels like important work. In fact, it doesn’t feel like work when it’s going well… it’s something I want to spend my time doing.

But I’ll start with the worst thing, since you ask - Which is when I feel I don’t have an idea that’s strong enough and a deadline is looming. My publisher, Puffin, have been very good about letting me sail past a few deadlines so that I can have the time to get to a place where I feel happy with what I’m giving them. Publishing can be very deadline focused, which is understandable, but good ideas come along at their own pace, need space to breathe and time to brew to become a book worth making. I know a lot of author/illustrators get very stressed by deadlines, me included, and I wish more publishers were able to be flexible and realise that the important thing is that a book is ready when an idea has been expressed fully, not when an arbitrary date has been met. A bad book won’t stay long on the shelves, a good one can stay on those shelves for decades.

There are many best things. The freedom to live your days in your own way and at your own pace is a big one for me. Spending each day being able to draw and think is another. One of the things I love about drawing is that you often don’t know where it will take you. Taking a line for a walk is always an adventure. I think of drawing as a loose form of thinking.

In earlier days I worked mainly as a painter in the fine art world. While I loved painting, I was not a fan of the dynamics of the art world and the end product - making a painting to hang on the wall of one rich person. Publishing is a much more democratic art form. A book that may have taken a couple of years to make is the price of a couple of coffees and is available to almost everyone (as long as we learn to value our libraries).

Taking a line for a walk is always an adventure. I think of drawing as a loose form of thinking.

I love the process of having ideas and letting them percolate over time, learning to filter them down and entwine them together into a book which must be entertaining and told simply so it can be understood by a 5-year-old, but also may have something to say to the grown-ups who read it too. I always try to speak to the entire audience.

Sometimes I feel I have something political I’d like to express. Finding a way to put that into a book, entertainingly and subtly, but so it also hits is a challenge, but perhaps a good way in our increasingly politically polarised world of saying something to someone on the ‘other side’ who may not want to hear it any other way. Children’s books can be a beautifully poetic way to put ideas out into the world.

Making books for children is to spend your life dealing with positivity. Children are an infectiously rewarding and positive audience. Reading to them and drawing with them is always an invigorating delight. The cherry on the cake is that the children’s book world seems to be almost entirely populated by lovely people who passionately care about what they do.

Thank you so much Ed! To find out more about Ed's work, visit his website or follow him on instagram. Find out more about the Power of Pictures programme and resources here.

Interested in taking part in The Big Draw? Registrations for our 2023 festival 'Drawing with Senses' are open now! Find out the benefits of becoming an organiser here and about this years sense-sational theme here.