With ongoing concern amongst the media about extended tablet use in young children, and the debated potential for harm, it seems the need to discuss and debate cognitive development is greater than ever. Drawing has proved, since the time that man became self aware, to be one of the most powerful communicative, and conceptual development tools known to man. One need only to look at caveman drawings and paintings to have an immediate sense of recognition, an intuitive flash, of our need to depict our environment as a way of understanding it. So what then, if anecdotal or early research would have us believe, happens if we collectively lose our ability to draw?

To even speculate seems alarmist and ridiculous as, quite rightly, most people cannot imagine, especially those with young children, not drawing or doodling something. But yet as we collectively launch ourselves into the iPad era, voyaging on our tablets like magic carpets, there are mutterings here and there that kids can no longer use pencils, and that coursework is no longer written with pen and paper. One cannot say the jury is out, for it has not yet convened, but for the long sighted or passionate it’s still worth saying: drawing matters.

The Laocoon discovered in Rome 1506

Almost everything made by man started as a drawing or sketch of some kind. Even the humble toilet roll or a bin liner began existence as a drawing, because at some point they had to be explained to somebody. One of drawing’s greatest strengths is its ability to convey complex ideas or messages in a clear and understandable way. Drawing has, and continues, to change the world.

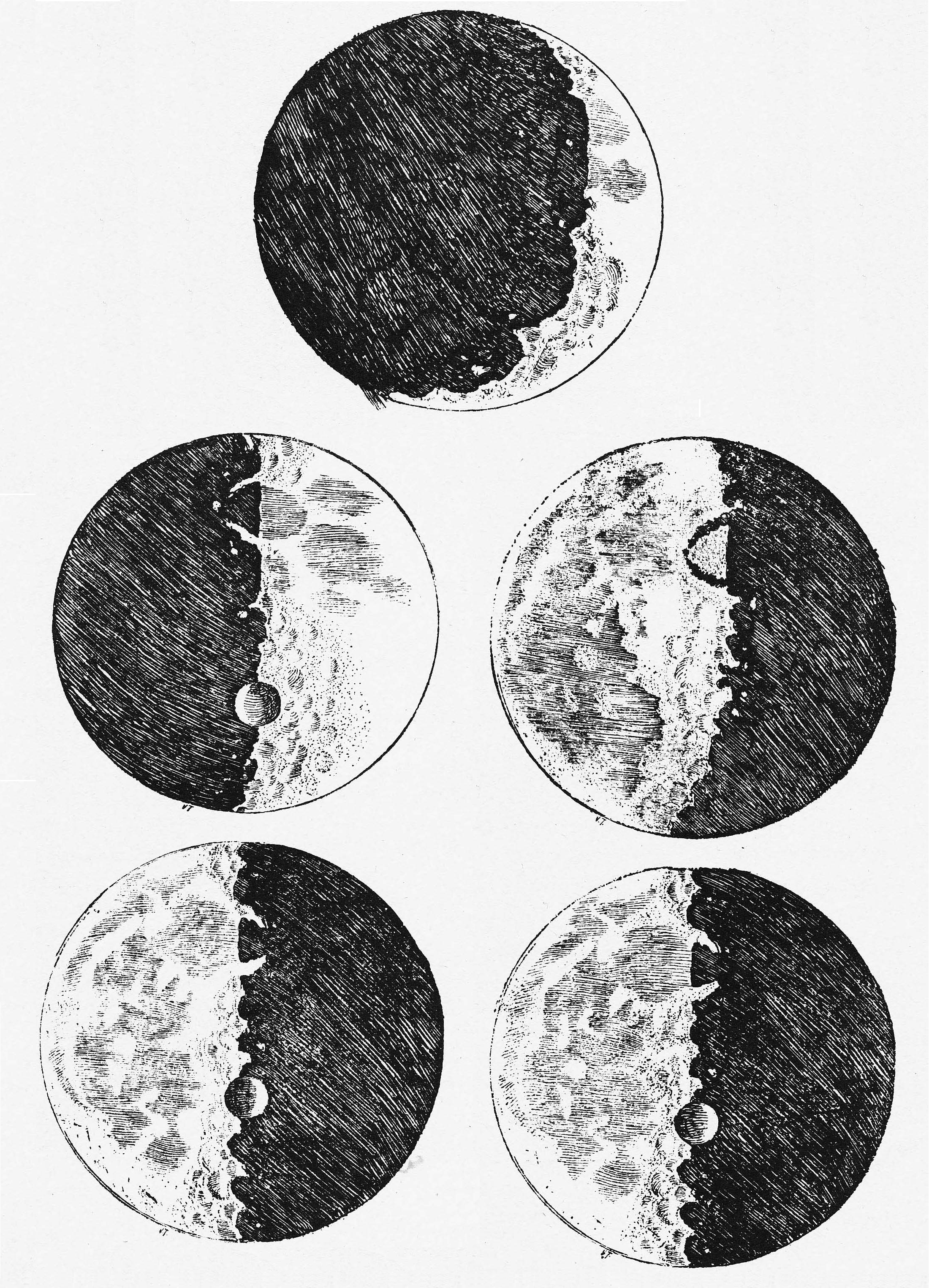

It is said that Michaelangelo, one of the most complete artists to have ever lived, upon witnessing the unearthing of the Ancient Greek sculpture of the Laocoon, in Rome 1506, began to draw it immediately. His drawings helped him internalise and comprehend this glorious sculpture as it emerged from the earth. This influenced his mark making and painting of the Sistine Chapel, and emboldened his vision for his architectural and sculptural designs. The value of drawing in this respect does not need to be stated, for the rest, they say, is history. Drawing, with wider art and Philosophy, underpinned the Renaissance, which has heavily influenced most of modern Western thought. When Galileo perfected the telescope in 1609 and donated it to the Doge of the Republic of Venice he not only secured a lucrative lifelong pay rise, but triumphed in over turning thousands of years of Aristotelian thought when he pointed it to the skies. Galileo’s drawings of the surface of the Moon caused a sensation.

The Moon, like the Sun, was once believed to be pristine and perfect, but on closer inspection proved to be pot-holed, cratered, and craggy: much like a celebrity without photoshop. The drawings caused passionate debate, which along with other factors, led to Galileo’s house arrest by the Church and subsequent demise. Without his drawings Galileo would not have been believed. This proved especially true in his drawings of Sunspots, and the Heliocentric view of Copernicus may not have been accepted without the documentation which underpinned the arguments.

But drawing is not a smudged and dusty object to be admired from afar in Museums, it’s a living and breathing thing that for better or worse is still changing our world. Zaha Hadid, one of the world’s preeminent architects, has spoken at length during her career of the profound influence the 20th century Russian artist, Kazimir Malevich, has had on her work, and in particular her drawing. Hadid, better known today for the sweeping sensuous lines of her futuristic buildings, is no slouch when it comes to painting and drawing. Hadid discovered Malevich in the 70′s whilst studying at the Architectural Association in London, and refined her concepts during her Masters at The Royal Academy in the early 80s. Hadid’s early virtuosic works of razor blade like shards of colour that swarm into architectural forms dazzle the eye and shake the mind. They are clearly influenced by Malevich’s paintings which display rectangular, linear, round or cuboid forms that seem to hang suspended or unattached to their canvases. These forms contributed to the imaginative leaps that Hadid has made in her own work today, and will therefore contribute to visions of her architecture in the future.

Malevich: Suprematist Composition, 1916

Zaha Hadid drawing influenced by Malevich at R.A

Jockey Club Innovation Tower of Hong Kong Polytechnic

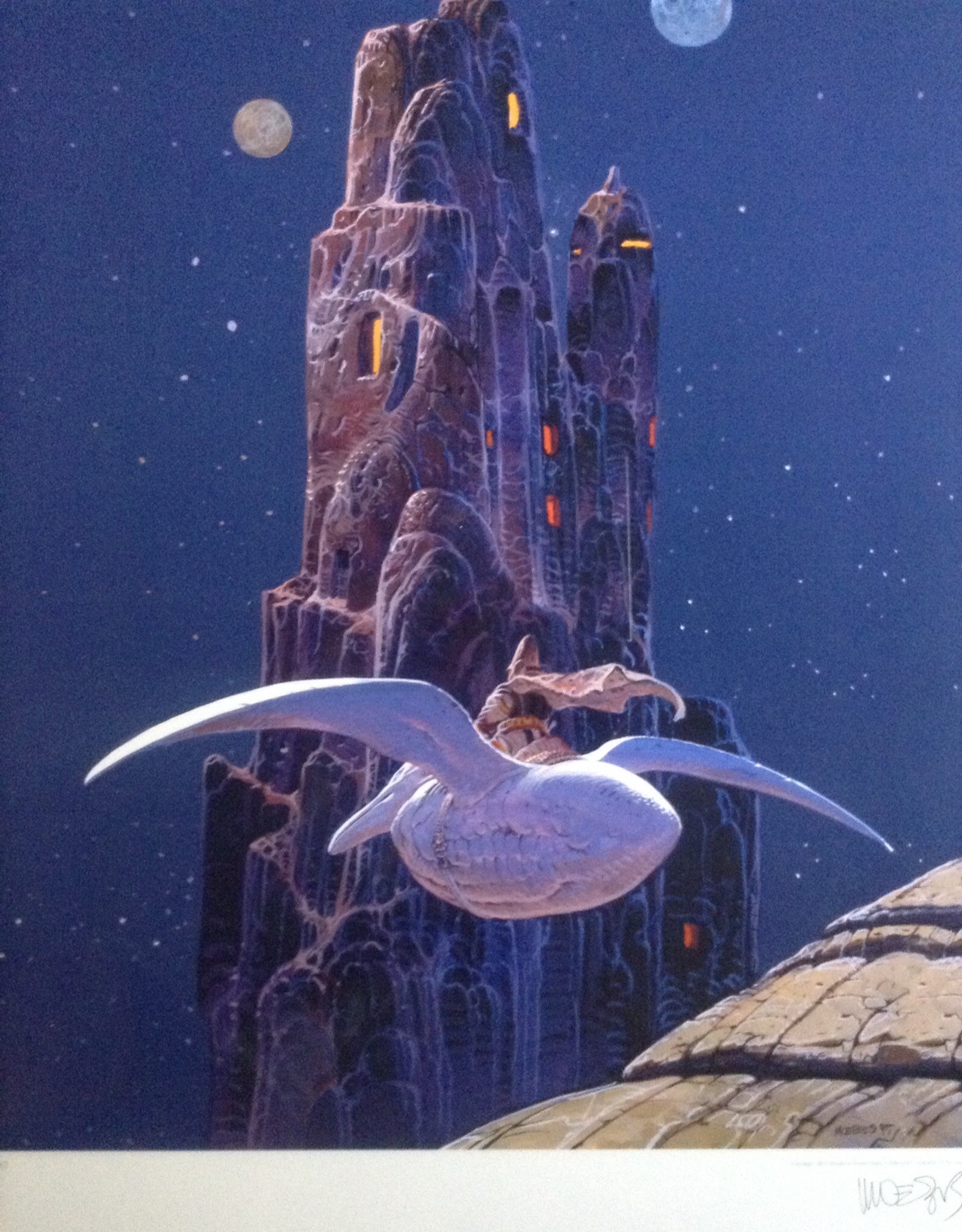

An undoubted contributor to an imagined future is the Director Ridley Scott. His iconic movies have made vast contributions to the public’s contemplations of a dystopian world. Without drawing, concept design for movies or games would be impossible. The film Alien is inseparable from the drawings of H R Giger. Whilst the film Blade Runner, since anointed as a sacrament of the Sci Fi genre, would not have lingered in the memory without the contributions of Ernst Fuchs. As is the case with the French comic Metal Hurlant, or the gorgeous and transcendent art of Moebius.

Drawing matters. The power of mark making, although intuitive and ubiquitous, cannot be overstated, as we would not have our modern world without it. It is far too early to say what effect tablets will have on physical drawing, but the more we draw the better. In this way we may imagine and realise our own worlds, and not have them imagined for us.

Technology is an indispensable part of progress and modern life, but even the iPhone and iPad had to be drawn first, and those things have changed us, and have in turn changed the world.

Moebius fantasy illustration

The last word goes to Zaha:

‘It took me 20 years to convince people to draw everything in three dimensions, with an army of people trying to draw the most difficult perspectives. Now everyone does 3D on the computer, but I think we have lost some transparency in the process. Through painting and drawing, we can discover so much more than anticipated’.

Zaha Hadid

Article written by Hogarth Brown for the Big Draw