Juliette Losq is an internationally exhibited, prizewinning artist whose work seeks to describe the borderlands on the fringes of urban developments, capturing the benign battles waged between man and nature. Losq’s renditions of the (sub)urban landscape are interrupted by the threat of an unknown presence. The dark recesses allow the imagination of the viewer to place where that threat might be lurking. This creates both an uneasy feeling and a visceral thrill.

Renowned for her use of watercolour, Losq works over the surface of her paintings repetitively, with successive layers both concealing and revealing imagery from those beneath. Losq experiments with complexity and scale, producing paper landscapes which she uses as maquettes for drawings, paintings and installations. Through this process of construction and reinterpretation, Losq references the ephemerality of the sites she visits, whilst developing an understanding of the model as a partially imagined, partially ‘real’, space that can transport the viewer conceptually from one place to another.

We fell in love with Juliette's intricate watercolour landscape works in 2019 when she was shortlisted for - and subsequently won - the John Ruskin Prize. We were incredibly excited to have a chance to catch up with Juliette a year on from this and find out more about her life and work.

Interview: Matilda Barratt in conversation with Juliette Losq.

Let’s start by talking a bit about your background - how did you come to do what you do today? What routes has your career taken?

I studied English Literature and Art History at Cambridge straight out of School. I then did a Masters in Art History at the Courtauld Institute in London. Thinking I would like to work in art insurance or valuations, I began working as an insurance broker in the City after this. After a few months I knew this was not for me, so I began saving up to study for an art degree, taking weekend and evening classes to build a portfolio. I ended up going to Wimbledon College of Art for my BA, which I thoroughly enjoyed.

Have you always had an interest in art?

I grew up on the outskirts of London and went to a comprehensive school in Romford. Art was always my favourite subject at school, and I studied it for GCSE and A Level. However, times were different then, and I was encouraged away from art school towards pursuing what was perceived as a more academic route. I did my A Level art at home in my own time, supervised by my Dad, who was an art teacher. I had a very supportive teacher at school who helped me with the art history component of the A Level in her spare time. When I later told her I had decided to study art history at university she was thrilled and gave me some of her own books.

Could you tell us a bit about your practice? The media that you use, the subject matter, the process, the inspiration...

Before I went to art school I tended to paint figurative portraits in acrylic – I had never been interested in landscape. In my first year I did an etching course. I took the opportunity to work with completely different imagery. On the train out to the East London suburbs where my parents lived I had always been fascinated by some of the semi wild landscapes that I could see out of the window. This led me to explore the Bow backs – a system of canals which were later developed into the Olympic site. When I was exploring them they were structurally almost unchanged since Victorian times, other than being very overgrown and covered in graffiti. They were almost deserted and extremely peaceful. I ended up being enormously inspired by this landscape and took a series of photos, one of which was developed into an etching. I enjoyed the process of building up the plate in layers, masking off the areas with resist. This became the inspiration for my drawing process, which is also built up from alternate layers of ink or watercolour and resist, creating a highly detailed tonal image that ‘develops’ from the paper and looks visually similar to an etching.

Watercolour is traditionally used on a small scale, and often viewed (wrongly, I might add) as a ‘preparatory medium’. What is it that draws you to watercolour, and why do you think it is important to challenge the preconceptions of this traditionally overlooked art form?

Initially I used watercolour and ink as these were the most suitable media to work with in order to develop this layered drawing process. As I progressed through art school I began challenging myself by making the drawings increasingly larger and more complex. I found that by working on a larger scale I was able to play with the degree to which the resulting image read as a figurative drawing vs. an abstract series of marks on a surface. So the large scale of the work is really a direct result of working intensively with the medium of watercolour and pushing the boundaries of the medium and my use of it.

After my BA, I studied at the Royal Academy schools (2007 – 2010). Using watercolour was supremely untrendy – people referred to me as “Watercolour Challenge”. There was a refusal to engage with the work on the basis of the medium, before even approaching the imagery. My feeling then, as now, was that this played into the traditional academic hierarchy of painting that had been in play since the eighteenth century, and was in fact an old fashioned attitude. Surely it should be acceptable to work in any or many media as a contemporary artist? It’s great to see that many younger artists now use watercolour as a part of their working process.

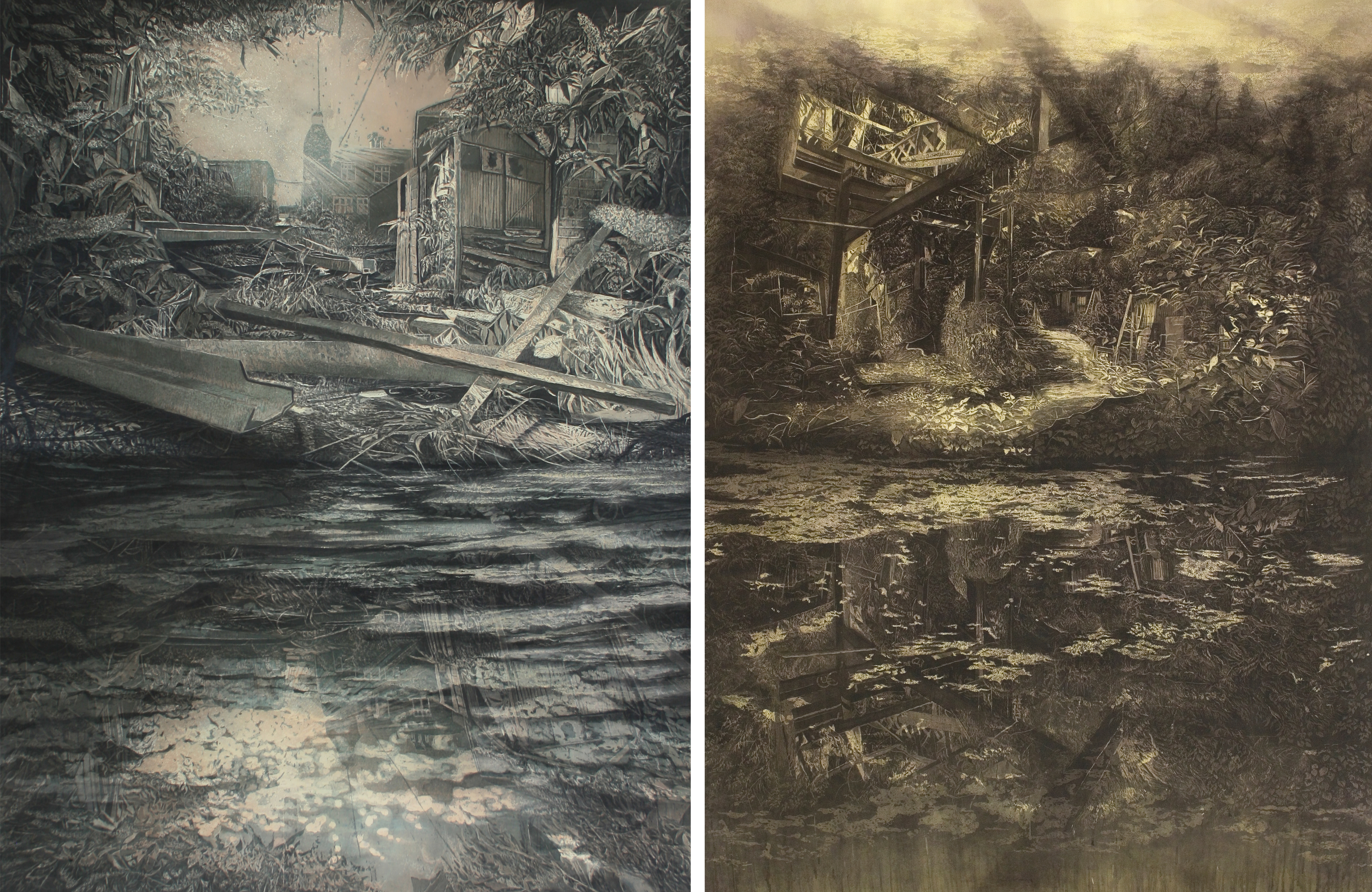

[Left: Polyorama, ink and watercolour on paper, 100cm x 120cm, 2019. Right: Teleorama, ink and watercolour on paper, 193.5cm x 145.5cm, 2018]

Your work often depicts overgrown, imperfect environments… Spaces that have been abandoned or neglected over time. How did your interest in urban and rural decay come about?

I think this is as a result of having grown up in the suburbs of London. There weren’t any attractive open spaces or woodlands to explore as a child so it was the overgrown and abandoned spaces that were interesting to me.

What do you hope to communicate with your work?

The kinds of spaces I am drawn to are, by their nature, transient and ephemeral. Especially in London, marginal zones are prime real estate waiting to be redeveloped. Through the process of reimagining and re-presenting these sites as large scale drawn environments, I am simultaneously preserving my experience of them and recreating them for audiences who may never experience them as real spaces. The drawing process and the process of making these pieces is extremely time consuming. In a sense this process monumentalises a subject matter that is inherently throw-away or lowly. I want people to spend time with these places. And for them to offer an alternative to the aesthetically clean, sanitised spaces that seem to predominate in modern cities and towns.

Do you work in a studio? Do you ever work outdoors? How does the space in which you work affect your creative process?

For the past 6 years I have been based in studios on Thames Islands – formerly Platts Eyott and now Eel Pie Island. Both of these are working boatyards, and Eel Pie Island is also a nature reserve. I’ve used Platts Eyott as a subject in several works, as it’s semi-derelict and full of interesting, unknown structures – at least unknown to me. I tend not to work directly from nature but I respond to the environment after the fact. So, for example, I only started making work based on Platts Eyott when I was no longer based there. So I think these places have an indirect effect on my work and feed into it over a period of years.

[Left: Corpusculum, ink and watercolour on paper, 156cm x 152 cm, 2013. Right: Labyrinth, elevation A]

What does a typical day look like for you? (If there is such a thing!)

I’m lucky to be able to walk to my studio so, after having taken my dog for a walk, on a typical studio day I arrive at about 10 / 10.30. I tend to work right through to about 6 / 6.30. I take a couple of short breaks but I work slowly, methodically and intensively.

Do you draw and paint on a small scale too, perhaps in sketchbooks? Do you ever use watercolour as a sketching medium to test out ideas or to simply pass the time?

I’ve never worked from sketchbooks by choice. I tend to use my studio wall as a kind of working sketchbook. I pin up photos that I have taken, art historical references, other people’s work. I don’t really sketch with watercolour – I tend to plan my work out as photo collages, both physically and using Photoshop. By the time I start painting or drawing I have already been through the visual editing process that many people work through in a sketchbook.

Our Festival theme this year explores humans' relationship with our living environments and ecosystems, encouraging drawing as a means of positive activism. What is your opinion on the role of art in communicating a message and bringing about change?

It’s been interesting, through the lockdown, to see how many people have turned to art as a means of getting through – either by making their own work or by visiting online exhibitions, virtual museums and the like. It’s ironic given the relatively lower status that art is still given to other subjects within the education system. However it seems to imply a psychological need for making that, perhaps, has not been fully recognised. Many people have felt trapped by their surroundings and have been looking to art as a means of escaping their immediate reality. This is certainly how I have always viewed my work. I’m not copying environments; I am recreating my experience of them to present something that is unique to me as an artist, but is speaking to those who view the work – about place, space, history, art history, the landscape.

[Left: Augurium, ink and watercolour on paper, 155cm x 165cm, 2019. Right: Oracle, ink and watercolour on paper, 155cm x 165cm, 2018]

Having experienced being persuaded not to study art and instead to go down a more ‘academic route’, what would be your advice for a young creative who feared that studying art may not be the ‘sensible’ choice?

I think as a nation we are fixed on ‘making choices’ that seem irreversible at a fairly young age. We limit our subjects at GCSE, further at A Level, and then further at degree level. But things are not necessarily set in stone and you can always end up as an artist via a circuitous route, as I did. Likewise you can have a full and rich experience at art school and, rather than working as a visual artist, this might permeate into your work within a totally different industry.

In other words, don’t listen to people who tell you that going to art school limits your options. Doing something that you are passionate about will not limit your options; listening to people who give you this advice might, though!

Thank you Juliette!

If you were inspired by this interview with Juliette and would like to find out more about her work, head to her website here.

Registrations are now open for The Big Draw Festival 2020: A Climate of Change! Find out more about the benefits of becoming an organiser here and other ways to support The Big Draw's mission here.