It’s rare to come across an artist like Venantius. Drawing isn’t just a hobby, a practice, a career, it’s a deeply embedded philosophy that he lives and breathes by.

We are very excited to shine a light on the story of the incredible Art Director, Designer, Illustrator and Chef, Venantius J Pinto and share his meaningful story with our audiences. We hope you enjoy the interview.

Interview: Devon Turner in conversation with Venantius J Pinto.

To begin, could you tell us about your first memories of drawing? Help us understand how you came to be as prolific as you are with a pen or pencil.

Being born a Christian in India within all of these other communities, there would be festivals where people would draw a “rangoli” on the floor – a drawing where they work with powders. I would see the way that the Hindus and Muslims would decorate certain things and I would always wonder, “why don’t we have that?” While that was going on, my Godmother brought me a set of coloured pencils. It was a small set, only twelve pencils, but we didn’t have paper. I was just over two years old and I found myself starting to draw on the threshold of my house. I started to draw this way, with my Godmother teaching me how to hold the pencils etc… That’s how it began, but it began through observation.

Later on, I would see my Mother draw. When I was in sixth or seventh grade, an Italian nun, Sister Zolia Castegnetti, FMA, gave me these calligraphy nibs – about 250 of them. She just gave them to me and said, “From now onwards, you have to work out a way to draw.” I didn’t know what to do with them, but my mother’s father used to write with these exact nibs; he was a scribe with beautiful copperplate penmanship. My mother bought me some ink and introduced me to the different weights. Then I came across an ink known as “cardinal ink” which was really as a black as a cardinal bird. I began to draw in history books, for example, if there was a Voltaire or Rousseau, I would draw these figures. Then I started to make these decorations to sell, to try to make some money. For these I needed to make large drawings so I began to use newspapers.

Things happened and began snowballing until the primary headmistress said that I should not go for elocution class but should instead be drawing the card for the week. The card was always drawn in chalk which was another new material for me and I gradually learned how to use the chalk and turn it at different angles so that it always remained sharp and never blunted. I realised that, even if you know very little, as long as you stick to the task - things can happen...

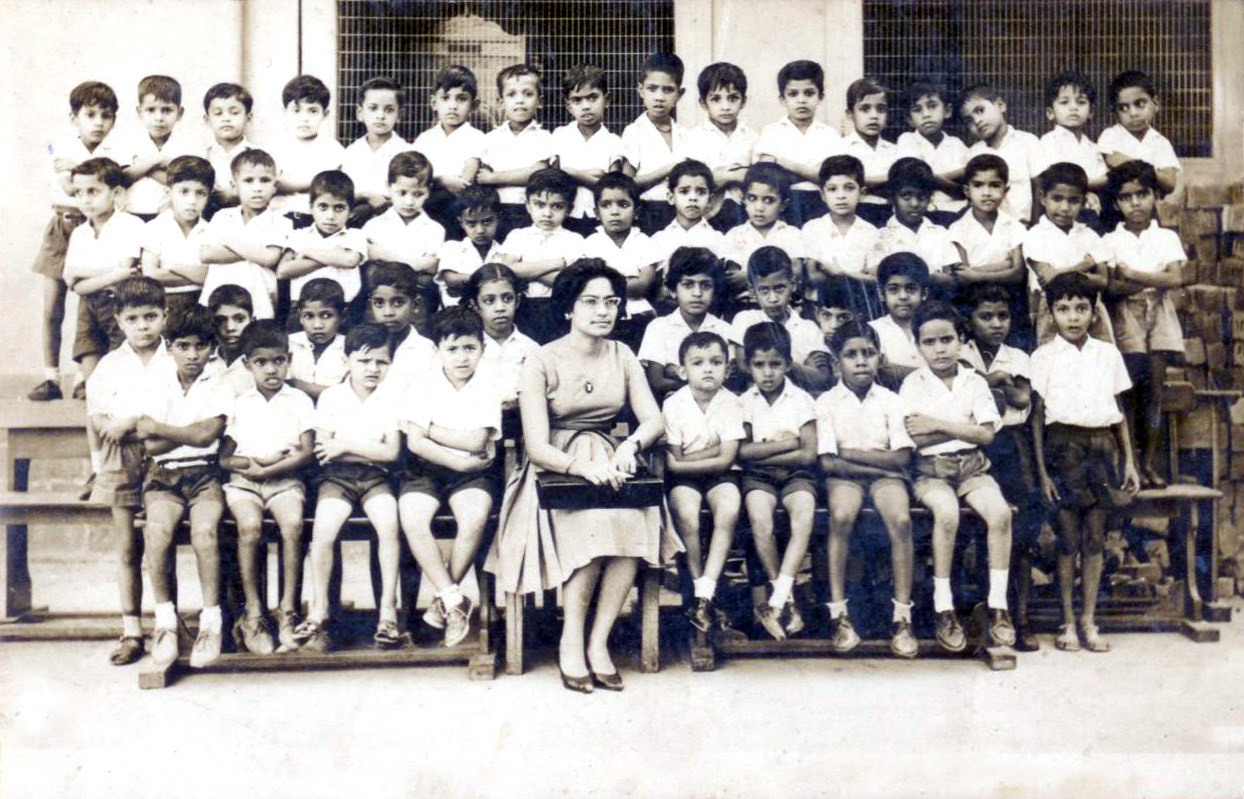

In the image below, Venantius is third to the left of the teacher, Ms.Dolly.

At The Big Draw, we always emphasize that people should focus on the importance of drawing to learn rather than purely learning to draw. Would you agree with that statement? How has drawing helped you to learn?

Absolutely. Although, the second part has to be fed correctly to people... A lot of times, if you aren’t mentored properly, people just assume that you want to draw in a certain style. For me, I’m the beneficiary of poor education, and I’m so happy about that. That forced me to look at and hone in on the skills that I had.

I’ve been looking at things from a semantic perspective as well. Semantic in terms of symbols as well as words. If you are looking at a word, you are looking at connected meaning and denoted meaning; if you ask people what “love” means, everyone would have a different answer. This is what fueled me. Then I began to look at signs. I was especially interested in signs made by homeless people - I was so fascinated when I saw people on trains with these signs. When I look at these things, other doorways open up. You are drawing with your hand, but your entire body becomes eyes. The thing is, whether you are using a brush or a pencil, the way you use it assists you in that learning process. It’s the realization of, “Ah, this is what it is.”

Tell us a bit about your process and the materials that you like to use as well?

By and large I use inks. When I was in school at the JJ Institute of Applied Art in Mumbai, I really couldn’t get the handle of watercolour. A lot of my classmates came from families where there was an artist and came with a certain body of understanding as well as sensibilities. I didn’t have any of that. All I had was somebody who was helping me buy materials. It was a very unique young couple that took an interest in me, and took it upon themselves to help me. I remember a time when they were in Japan - she wanted to buy a dress, and her husband said to her, “Ok, so Venny wants a brush, and you want a new dress, why don’t you make the decision?” Of course, I got the brush.

How did you meet this couple who took an interest in you and your art?

They were a family that did a lot with the church that we were a part of in India, and she was an Anglo-Indian at that. Her name was Yulette and she had come from Calcutta, and was very vivacious. My eye has always seen grace within other people, and I saw it in her. That’s how we met and then she commissioned me to do some pictures for her and she amassed a small collection of my works.

After she got married, she asked if I would paint the inside of her bedroom door. I wasn’t picky about paints at this point and so I managed to collect some poster paints and some polyurethane - that was all I could scrape together at the time. This relationship continued, and they are the ones that helped me to study at the Pratt Institute – that’s a lot of money, a sickening amount of money! At this time I became acquainted with artist-grade paint and found myself becoming fond of them and spending lots of time in art stores assessing the paints, nibs and brushes for far too long.

Written language – letters with all of their organic lines and dots can be fascinating to draw. How does lettering fit into your practice? Can you tell us about your interest in Shodo (The Way of Writing)?

Lettering is something that I did for the church clubs since I was extremely little. I would get something like 15 rupees for it. Almost all of my work is different. Once I do something, I move on. Doing those posters for the school and drawing on the board led to more work for funerals, creating custom crosses and things. I would paint on them and then add my lettering. Priests would call on me to do things in their libraries as well. This meant that I learned words like pedagogy, mariology etc...

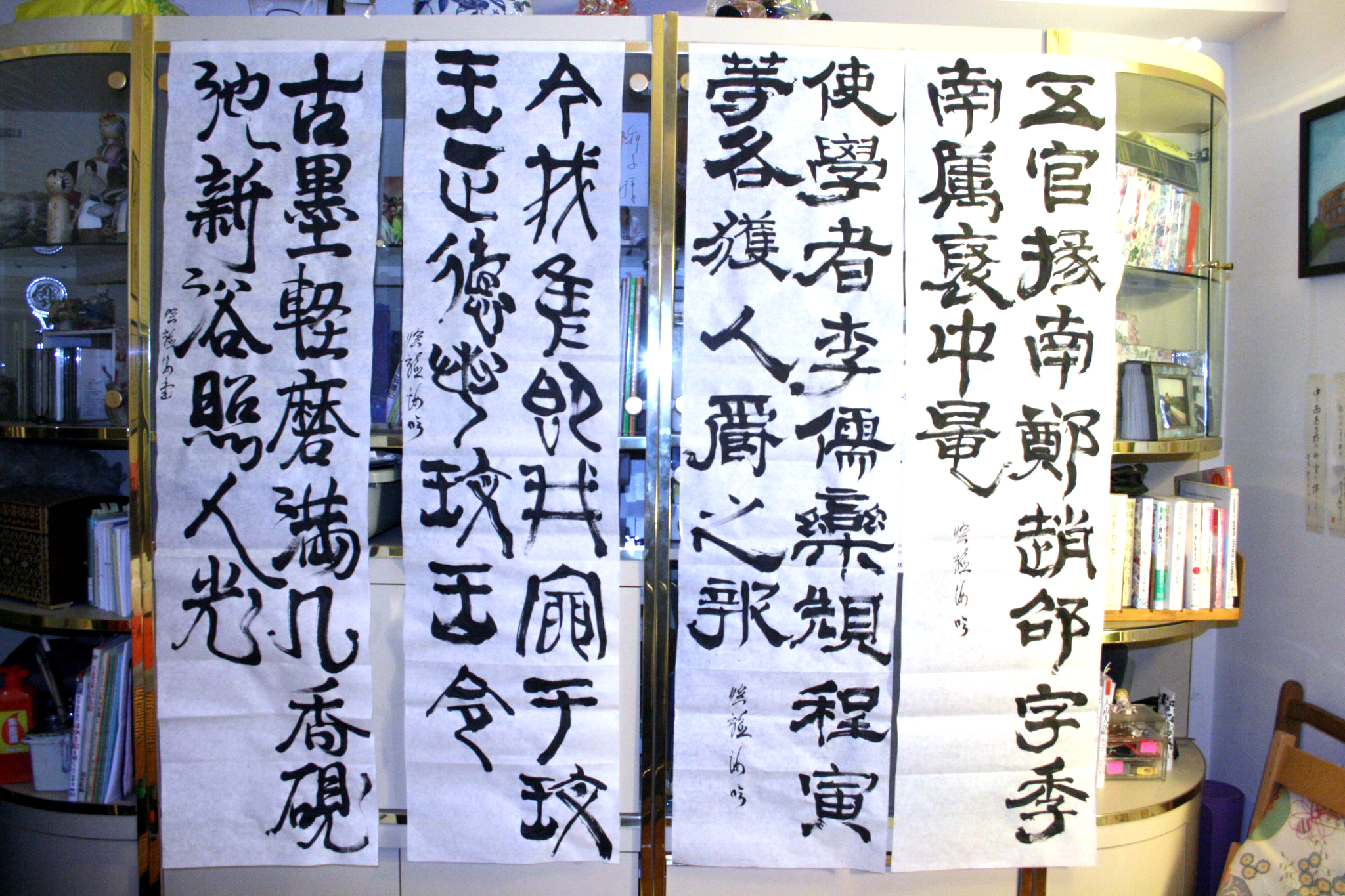

The calligraphy came about years ago when I was interacting with some martial arts people. There was a sagist guy sitting there who was an expert in calligraphy and friends encouraged me to pursue this as an artist. We began with stone inscriptions; as it was done thousands of years ago in China, this was complex, but I found somebody who knew a teacher who would help me. I ended up learning a lot of the techniques. There are five kinds of calligraphy: kaishō , gyoshō , soshō , reishō and tenshō. I probably have about 150 dictionaries, out of which 60 are directly related to Japanese and Chinese calligraphy. It’s all about how you use the brush, you almost have to pretend that you are using a knife or something.

Your keen interest in philosophy and humanity also have an important place within your practice. How have you used mark-making to explore mans’ place in the cosmos and other great mysteries of life?

We are a speck in the cosmos. And we have placed ourselves unknowingly at the centre. There are billions of galaxies... The sheer thought of this - though exciting to some - is extremely frightening to me. I often question, “What is the place of man in this world?”

I think what we are trying to do in general is to perfect ourselves. As Agnes Martin said, “In our minds, there is awareness of perfection and when we look at it, we see it, but how it functions is mysterious and unavailable to us.” What we can know for sure is what touches us and what moves us. What is it that allows artists to do what they do? What allows artist educators to do what they do? Is it strictly about earning a living?

I see the cosmos as a reflection of ourselves. There are four components that are really necessary: us physically; our mind; emotion; and life energy. When these four things come together, your awareness improves. I don’t think as of yet I have any specific answers because, who am I really?

In addition to being an artist, you are also a chef. Can you tell us if there has been any crossover between cooking and drawing for you? Do smells inspire you to sketch? Do certain recipes taste better when they are drawn out?

I’m not a chef in the true sense, but in the French Brigade system, I am known as a fry chef. Within the American system, I’m a cook. However, if someone like Gordon Ramsay took me under his wing for three months, I would zap the daylights out of him. I work at the Barclays Center which is a stadium that houses two teams, ‘The Brooklyn Nets’ and ‘New York Islanders’. We are given estimates of how many people are in the house and have to make the food accordingly. It’s all happening in a blur because of the fast-paced nature of the environment.

I've been fortunate to try quite a bit of food. I’m not always very aware of it at the time, but when I’m working on something and eating something in particular, the art changes. If I’m eating something sour, my hand moves one way. If I see or smell things that are very pungent, I flick the brush in a particular way. I hardly have sugar, but it causes me to think in lyrical terms.

Finally, WHY do you create? Who do you create for?

I have a very interesting thing that I wrote in one of my papers. “To engage with your own thoughts and those of others, a larger consciousness, a sympathetic space, the why of things, occurrences, stirrings, provocations, the space between one’s legs, the tilt of a head, spaces that people simply seem to inhabit”... If you are doing a drawing where you are operating the idea that you need to create a space that’s sympathetic, like Loie Fuller or Isadora Duncan... How do I go about it?

In modernity we have lost a lot of things. I often wonder how to bring up these ideas - ideas that may have been lost in time - and make them new again. Mary Magdalene with her chin on the knee of Jesus; Can I do this? Is there a way?

Sometimes, you don’t have a very good reason, but something nags at you, gnaws at you, and you think, “This thing is trying to get out into the world” and once it’s out there, it’s gone. As an artist, you are like the conduit, a catalyst for something to get out into the world. It’s like a birthing. A birthing on your own terms, at least.

If you were inspired by this interview with Venantius and would like to find out more about him and his work, click here.

Registrations are open for The Big Draw Festival 2020: A Climate of Change! Find out more about the benefits of becoming an organiser here and other ways to support The Big Draw's mission here.